Beyond Little Rock’s Integration Battle: The Wider Implications For America And Global Realities Today

The Oasis Reporters

March 6, 2020

By Greg Abolo

I made a call two weeks ago to Little Rock in Arkansas, a state where President Bill Clinton was once a State governor. Unknown to me, a meeting of stakeholders was ongoing at Central High School, where the battle for integrating schools in the United States of America began, that caught global attention back in the late 50s. It is the deep and engrossing story of 9 black students with the courage and conviction of how right their cause was and they therefore defied all odds to be at Central.

Here’s an account of how journalist Lina Mai captured the story on September 22, 2017 and we acknowledge Time Magazine for this reproduction.

‘I Had a Right to Be at Central’: Remembering Little Rock’s Integration Battle

It was late September 1957, and students at Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas had been in class for three weeks. Everyone, that is, but 14-year-old Carlotta Walls and eight other teenagers who were to be Central High’s first black students. They had been prevented from entering the school by an angry mob of citizens, backed up by a group of Arkansas National Guardsmen.

But on Sept. 25, under escort by Federal troops, Carlotta and her classmates walked up the front steps of Central High and into history.

They became the highest-profile black students in the United States to integrate a formerly all-white school. This month, Little Rock will celebrate the 60th (now 63 in 2020) anniversary of that pivotal moment in the civil rights movement by honoring the students who became known as the Little Rock Nine, with events including speeches by eight of the students as well as former president and Arkansas governor Bill Clinton.

For Carlotta Walls LaNier, the anniversary is a chance to raise awareness about the fight for racial equality. “Our purpose is for people today to understand why [kids] are sitting in classrooms with those who don’t look like them,” she tells TIME. “It was due to our success at Central 60 years ago.”

The School Year That Made History

Three years earlier, the Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that school segregation was unconstitutional, but many areas, like Little Rock, refused to put that decision into action.

During the previous school year, Carlotta Walls had been a student at an all-black junior high school, where her homeroom teacher was aware of a district-wide decision to gradually implement the changes that would be required. That teacher asked the students if they were interested in attending Central High, the city’s most prestigious high school. Carlotta jumped at the opportunity and signed up without asking her parents. “I knew what Brown meant, and I expected schools to be integrated,” LaNier, now 74 (74 in 2020), says. “I wanted the best education available.” It wasn’t until her registration card arrived in the mail in July that her parents found out she had enrolled.

But being enrolled in Central High and attending classes were two different things. On the first day of the new school year, angry mobs of segregationists confronted the nine students on their way to Central. The protesters shouted racial slurs and chanted, “Two, four, six, eight, we ain’t gonna integrate.” As the teens approached the school, the state’s National Guardsmen—dispatched by Governor Orval Faubus to enforce segregation, despite the Supreme Court’s ruling—blocked them from entering.

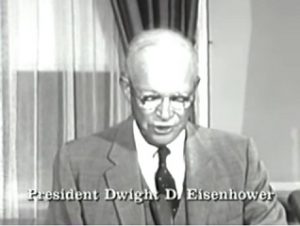

President Eisenhower was outraged. “Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of the courts,” he said in a televised speech on Sept. 24, 1957. The president sent 1,200 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division to protect the teenagers.

But, though each of the Little Rock Nine was assigned a personal military escort for the duration of the year, the troops were not allowed to enter classrooms, bathrooms or locker rooms. As a result, LaNier, like the eight other black students, endured daily indignities, threats and violence. Students spat on her and yelled insults like “baboon.” They knocked books out of her hands and kicked her when she bent down to pick them up.

Despite the constant attacks, Carlotta refused to cry or retaliate. “I considered my tormentors to be ignorant people,” she says. “They did not understand that I had a right to be at Central. They had no understanding of our history, Constitution or democracy.”

Harrowing images of the students dominated national news coverage. Central High became emblematic of the nation’s struggle for racial integration. Little Rock was “the first really public and visible test case of whether Brown is going to succeed in the South,” says Michael Brenes, a historian and archivist at Yale University. As LaNier wrote in her memoir, A Mighty Long Way, “I learned early that while the soldiers were there to make sure the nine of us stayed alive, for anything short of that, I was pretty much on my own.”

And attending class in 1957 wasn’t the end of the fight for the Little Rock Nine, either. The next year, Governor Faubus closed all of Little Rock’s public high schools to avoid integration, leaving 3,700 students stranded. Carlotta was not deterred, completing 11th grade by taking correspondence courses. Just a month before receiving her high school diploma, a bomb blew through her house. Carlotta made a point of returning to school the following day. “If I had not gone,” LaNier told NBC News in 2015, “they would have felt like they had won.”

Little Rock wasn’t the only city to resist school desegregation following the Brown decision, but the stark images that emerged from that particular conflict fueled public support for desegregation around the country. “When people saw what was going on, they were genuinely shocked and horrified,” says Brenes. “I don’t think you would have had the growth in the Civil Rights Movement if not for Little Rock.”

The crisis at Central High School did lead to increased school integration throughout the nation. But 60 years later, many public schools in the U.S. are still divided. The number of schools isolated along racial and economic lines more than doubled over a 13-year period ending in the 2013 school year, according to a 2016 Government Accountability Office study. What’s more, the report found that schools with higher concentrations of black or Hispanic and poor students offered fewer educational opportunities, including science, math and college-prep classes.

“The statistics are dire,” says Brenes. “This is not a Southern problem anymore. This is a national problem.”

As national attention turns back to Little Rock, LaNier views the anniversary of the Little Rock Nine walking through the doors of Central High School as both a celebration of progress and a call to action.

“We still have work to do,” she says. “We have to make sure the progress we’ve made is not reversed.”

Lina Mai is an Education Editor at TIME Edge.

Such a deeply engrossing story to read there.

But when the situation is examined today, the United States of America seems to have benefited enormously from the struggle to integrate at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Take the issue of the Valedictorian tradition in American schools that is facing a big challenge today and find out why more and more schools are doing away with the valedictorian honor as captured by John Thelin, the author of:

A History of American Higher Education and

University Research Professor, University of Kentucky.

John Thelin writes in The Conversation and republished in The Oasis Reporters, inter alia that “As college and high school graduations take place, thousands of select students will step to podiums to deliver their graduating class’s farewell remarks at commencement ceremonies throughout the United States.

These students – usually the graduating seniors with the highest grade point average, or GPA – are recognized with a formal title: valedictorians.

Though the tradition goes back to colonial times, the validity of valedictorian honor is increasingly being called into question. A growing number of schools are changing how they bestow the honor or doing away with it altogether.

For instance, this is the last year there will be a valedictorian at William Mason High School, an Ohio school that is one of the best regarded in the nation. School leaders announced May 9 that the school would no longer have a class valedictorian or salutatorian as of next year, citing “unhealthy competitiveness among students”.

As an education historian, Mason High School’s decision underscores what I see as a long-standing problem in American education: Our emphasis on competition and awards in academics sometimes leads to problematic measurements of learning.

A question of honor

Recent news reports call into question whether the valedictorian honor is truly about merit or hobbled by biases of race and class.

Indeed, in a growing number of cases, students who have earned the top grades in their graduating class – but who happen to be more have darker skin hues than their peers of European descent – are finding themselves being asked to share their valedictory glory with other students”.

Now here we are. The darker skinned students who were once being segregated against now top their classes and emerge class valedictorians.

For example, in 2010, Katie Washington, of Gary, Indiana, was celebrated for “making history as the first black valedictorian from the University of Notre Dame.” The then-21-year-old biology major had a minor in Catholic social teaching and an overall 4.0 GPA. Today, Katie Washington Cole is a psychiatrist in Chicago. You may call black rising, an awakening from the days of slavery to the top of the academic class. So who is superior to the other today unless we say that all human beings are created equal ?

The Globe’s reporting shows how academic achievements usually have some connection with opportunities and privileges. Talent counts, but it coexists with non-merit factors of race, gender, income, connections and luck.

Honor eludes diverse students

Some black or Hispanic students report being unfairly excluded from holding the valedictorian honor.

For instance, Jasmine Shepard, a black student from a school district in the Mississippi Delta, is suing the school district for forcing her to share the valedictorian honor with a white student in 2016. According to her lawsuit, the white student had a lower GPA. Similar cases were filed by black students in 2017 and 2011, although the 2011 case was ultimately dismissed.

In 2018, Jaisaan Lovett, the first black valedictorian at University Preparatory Charter School for Young Men in Rochester, New York, was denied the opportunity to give the valedictory address – a decision that may have stemmed from his history of protest at the school.

Earlier this year, Natalie Ramos, a graduating senior from Jesse Bethel High School in Vallejo, California, protested on social media when she was told she would have to share the valedictorian honor with nine other students. She was particularly upset because she was to be the first Latina valedictorian at her school. The school principal reversed the decision after GPA calculations had been “updated” and announced that Ramos would be the sole valedictorian.

A researcher somewhere said that for every 100 black doctors you find in America today, 70 percent of them are from Nigeria, a country with very poor infrastructure and a collapsing medical facility everywhere while its leadership do not treat common ailments in Nigeria’s health facilities. They fly abroad to do that.

But does America need the services of Nigerian doctors ?

Yes.

Withdraw all Nigerian medical personnel from health facilities in Atlanta Georgia for instance, and healthcare crumbles immediately.

But then, who wanted blacks to go to school about a 100 years ago ?

Credits:

Lina Mai

Time Magazine

Prof. John Thelin