Black Coffee And Enhle Ruling Sends A Clear Message: Customary And White Weddings Are Equal In South Africa

The Oasis Reporters

October 25, 2025

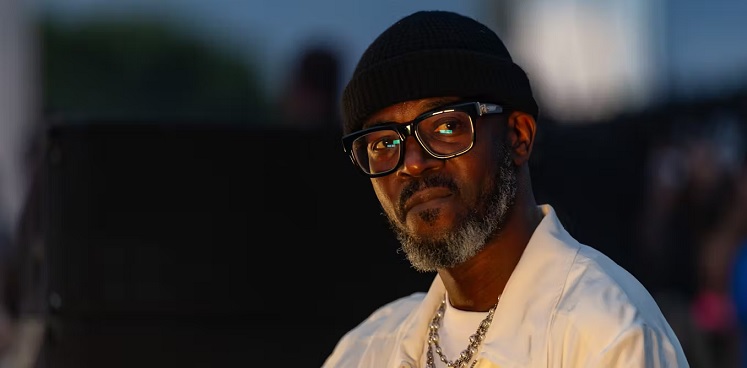

Grammy Award-winning deejay and producer Black Coffee performing in London in August. Shane Anthony Sinclair/Getty Images

Anthony Diala, University of the Western Cape

South African actress and businesswoman Enhle Mbali Mlotshwa has won a victory in the Johannesburg High Court. It ruled that her customary marriage to music star Nkosinathi “Black Coffee” Maphumulo was valid, declaring their later civil marriage and antenuptial contract null and void. Mlotshwa is now legally entitled to half of the couple’s vast estate.

A scholar of legal pluralism and specialist in customary law marriage, Anthony Diala, answers our questions.

What is customary marriage and how does it fit into South African law?

A customary marriage is a union between a man and one or more women, which is concluded in terms of African customary law. This means that the marriage must comply with traditional customs and ceremonies like negotiations between families, payment of bride wealth (lobolo), and handing over of the bride to the groom’s family.

Although customary marriages are between individuals, the clan is heavily involved. In the rustic societies where indigenous customs arose, marriage was originally between the families of the couple.

A customary law union is recognised as a valid marriage by the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 1998 (RCMA). It makes a customary marriage automatically in community of property unless the parties exclude it in a contract before the marriage is concluded. Community of property means that all wealth and liabilities that accrue during the marriage are shared equally between the parties if they divorce. This is the default position for all marriages in South Africa.

South Africa operates multiple legal systems because of colonialism. Dutch and British colonisers imposed their own laws and used them to regulate indigenous African laws. When democracy replaced colonialism and apartheid in the 1990s, indigenous laws received constitutional recognition. But they remain regulated by western ideas.

The Recognition of Customary Marriages Act transplanted some western principles in the Divorce Act and the Matrimonial Property Act into customary law marriages. Africans who cherish indigenous culture regard these principles as foreign to marriage customs. They resent these principles because they are inspired by European colonialism.

What were the arguments for and against Mlotshwa’s bid?

The parties contracted a marriage in May 2011 in terms of Zulu customary laws. After that, in 2017, they contracted a civil law marriage. This later marriage included an antenuptial contract. This document underscores the dispute.

An antenuptial contract is a legally binding agreement undertaken before marriage, usually to regulate finances in the union. It allows parties to decide how to share their estate. For example, one partner may refuse to share the wealth they accumulate during the marriage, or give only part of the money they make to their partner if they divorce. (When this agreement is adopted after marriage, it is called a postnuptial contract.)

Black Coffee claimed that their 2017 antenuptial contract excluded the default law of community of property. This means their assets and liabilities were not to be shared equally. So this claim implied that their civil marriage in 2017 replaced the 2011 customary law marriage.

His argument relied on the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, which allows a “change of marriage system”. Couples in a customary marriage are also allowed to have a civil marriage if they aren’t in another customary marriage with someone else. The act states that couples who make this switch do so “in community of property and of profit and loss unless such consequences are specifically excluded in an antenuptial contract”.

However, section 7(5) of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act and section 21 of the Matrimonial Property Act require a judge’s approval for any change of marital system to be enforceable.

Mlotshwa claimed that their civil marriage did not legally replace their customary marriage. Also, she claimed their antenuptial contract did not meet legal requirements of informed consent and court approval. Judicial approval essentially protects the marital property regime of an earlier marriage. In sum, she claimed their customary marriage was not altered by a court-approved postnuptial contract, and was in community of property. Thus, she was entitled to half of the assets they had accrued since 2011. The court agreed.

What does the case tell us about South African law? Does it change anything?

This case affirms the legitimacy of customary marriages in South Africa. Beyond this, it settles a longstanding question: how does a civil marriage between parties affect their earlier customary marriage to each other? Historically a later civil marriage legally replaced the customary marriage. But the marginalised status of customary marriages has been ended by the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act.

Regrettably, the marginalisation of customary marriages bred a tendency to engage in what is called “dual” or “double-decker” marriage. Many Africans who have a customary law marriage go on to undertake a “white wedding”. Some do so because of Christian influences. Others do so from legal considerations, as they falsely believe a civil marriage offers more legal protection.

But a dual marriage is unnecessary. Customary and civil marriage have equal validity in South Africa. Importantly, both carry the same default community of property. Previously, the issue centred on which marriage came first. Now, the issue is what type of contract accompanies a marriage.

What’s likely to happen next?

If Black Coffee appeals against the judgement, he’s unlikely to succeed unless he successfully argues a technicality in the High Court decision. For me, the judgement passes a clear message: all marriages are legally equal in South Africa.

The Recognition of Customary Marriages Act gives judges the same powers to handle matrimonial property as they have in civil marriages. Thus, there is no difference between a customary marriage and a civil marriage regarding the division of matrimonial property.

Is the judgment a welcome development?

The judgment highlights tensions between indigenous and western marriage systems. But it protects women married under customary law from attempts to lessen their marital property rights through agreements that fail legal requirements of informed consent or advice. Had Black Coffee won, women who help to build marital wealth would remain disadvantaged.

Significantly, indigenous norms of marriage do not recognise community of property. This is because these norms emerged in agrarian, patriarchal societies.

In these societies, family wealth was generated collectively and mostly managed by a male family head. Women lacked marital property rights simply because social organisation discouraged individual property rights.

Ultimately, the judgment reflects convergence between indigenous customs and statutory laws. Above all, it demonstrates the power of liberal law reforms in South Africa.![]()

Anthony Diala, Professor of African legal pluralism and Director, Centre for Legal Integration in Africa, University of the Western Cape

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.